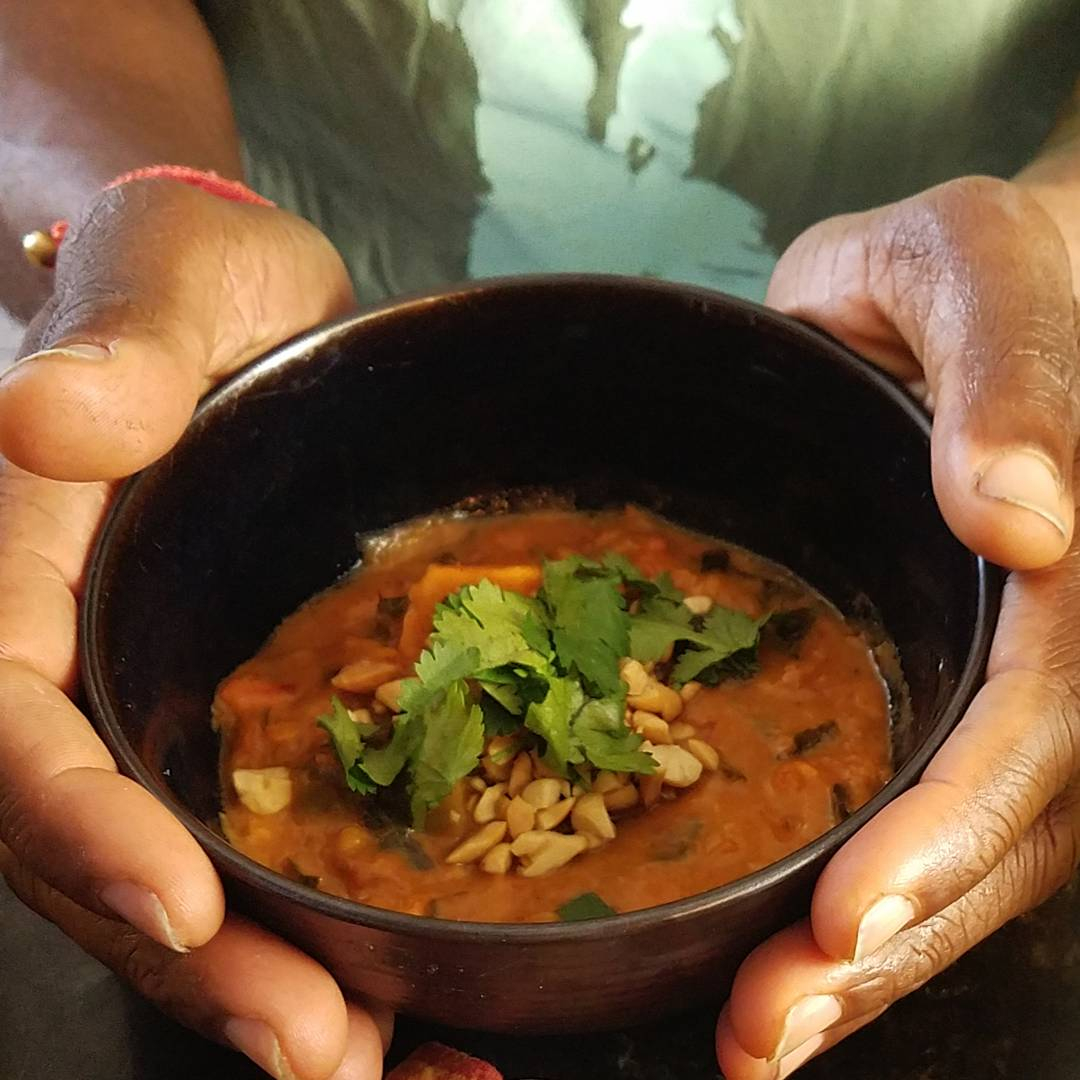

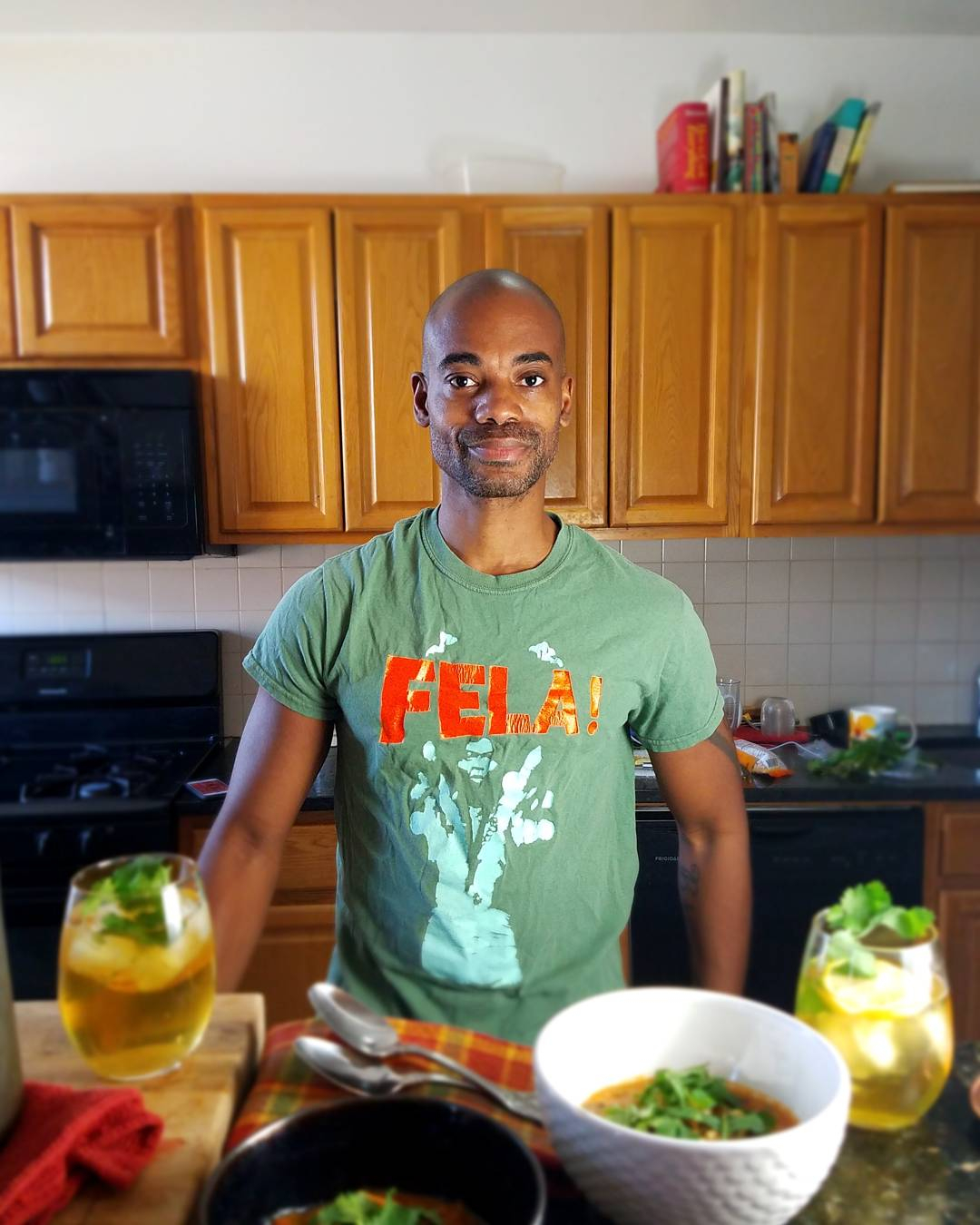

- Delano Burrowes prepares an African Peanut Stew | Photography by Kelly Torres

When I tell people I meditate, the response is almost always the same: “I could never meditate. It’s too hard to quiet my mind and sit still.” There’s still a very pervasive idea that meditation can only happen while sitting cross legged with a beatific smile. And if a state of nirvana is not reached, it’s somehow a failure, a goal not reached.

But meditation is simply about being as fully present as possible for everything good, bad and mundane. Or better yet, it is to not apply words like good or bad, and instead see layers in every experience outside of the simple terms we use. To look at them in a different way so that we no longer ascribe words like good, bad, and mundane to them, but instead see complex layers to all experiences.

- Delano Burrowes prepares an African Peanut Stew | Photography by Kelly Torres

Cooking can easily fall into that same result-oriented categorization for me. Eating the food is good, cooking is mundane. And certain tasks, like peeling potatoes and washing dishes, are bad. But what if I stop the mind that can only see those carrots and sweet potatoes in their future form of North African Peanut Stew, and instead see them in their current form and all the acts involved in their transformation as necessary and valid? How can that change my cooking experience, my cooking on a micro level, and the way I look at all parts of my life on a macro level?

I pick up my bright orange bowl on the kitchen island, full of potatoes, garlic and bananas. There’s a large chip on the side, exposing the chalky white ceramic beneath. An old roommate hated the bowl and tried to hide it, but I found it and put it right back where it belonged. The bowl has been with me for many years and we’ve both stayed (relatively) bright despite our imperfections. OR, maybe because of them.

The garlic skin crinkles in my hand. I pick it up and deeply inhale, pungent aromas hitting my nose with bitter sharp force. My old white knife begins chopping, dulled edges pressing as much as cutting the garlic. Putting it aside I quickly start chopping the onion, knowing the burning will soon begin but also accepting that discomfort will ease as it always does. I try to be present for the tears, to feel it outside of the concept of “pain,” and notice the underlying sensations that make up that word: Tension. Tightness. Throbbing. The way my mouth tightens in response to the burning.

The onions and garlic are placed in the peanut oil that is warming over high heat and the three commingle, creating a soft warm smell in my kitchen. My saliva glands begin to activate as I think about the meal I’ll be eating. But that is not now, so I stop and close my eyes, the smells bringing me back to the present. If I am already eating the meal in my mind, imagining how delicious it will taste, then I’m concentrating all my joy and happiness on the future, whether it be minutes, a week, or a year away. What about now? What am I doing right now that I can look at and not think of as work but part of the creation of something, be it a meal of the parts of my life that all seem so frustratingly random but will hopefully gel into something wonderful, a recipe not yet created?

- Delano Burrowes prepares an African Peanut Stew | Photography by Kelly Torres

I breath them in deeply. I focus on that breath, how my chest rises as I inhale and belly relaxes during the exhale. My breath is with me wherever I go and is the easiest way to bring me back to the moment. In the kitchen it also takes in all that.

Salt and pepper are added to the cooking alliums. I think of watching my Southern mother prepare fried chicken and seeing her add salt and pepper to the white flour, how all those ingredients came together to make my favorite dish. She always seemed to have all the time in the world when she was cooking, even though she was raising and feeding two children and three step-children. But when she was cooking everything was slowed down. She never used measuring cups but somehow everything always tasted exactly the same and it always tasted perfect. No fried chicken will ever be as delicious my mother’s.

Crushed red pepper and thai chili sauce are added. I can taste the slightly sweet heat in my mouth even though I’m only smelling it, deep in the back of my nostrils. All the senses are connected in such an overlapping way, combined with memories. Why do I love mayonnaise but not mustard? Why do I eat carrots almost every day but red cabbage makes me nauseous? What other experiences are combined with the memories, like the garlic chile mixture cooking on the stove?

Vegetable broth and sweet potatoes are added and brought to a boil, then reduced to simmer. I look around my kitchen. I’d love to say I follow the “clean up as you cook” rule, but I rarely do. There are knives and cutting boards to wash, counters to wipe, and ingredients to put away. Cleaning isn’t in my natural DNA and it’s a challenge to not rush through it as quickly as possible.

- African Peanut Stew prepared by Delano Burrowes | Photography by Kelly Torres

At my first meditation retreat I was told to bring mindfulness to everything I do, washing my face in the morning, brushing my teeth, mopping the floor, everything. Each of us had an assigned chore and we were told to fully concentrate on the task. And since the retreat was completely silent, we could bring all our senses to the act with no escape from a TV in the background, a telephone, or Facebook. I now bring that to cleaning.

I watch the water run into the sink, noticing the feelings in my body when I want the sink to fill at a faster rate. What does impatience feel like? I can feel it in my temples and in my jaw, one throbbing and the other clenched. Awareness of emotions that are uncomfortable is like Kryptonite. They lose their super abilities and are made human. The water sounds like a waterfall, like Bash Bish Falls in Western Massachusetts where I grew up. What first appeared as an almost solid stream is now made up of shapes, bodies slowly dancing for an audience of one. I turn off the faucet.

Tomatoes, collard greens, and peanut butter are added to the broth mixture and then it’s back to cleaning. Different sponges or scrubs create different sounds. What if I apply pressure here instead of there? The texture of the cooling water has changed, the silkiness of the dish liquid less noticeable.

Edamame is thrown into the pot, the last ingredient. A few beans miss the pot and I pop them in my mouth, biting down on the chalky hardness. I don’t like raw beans but whenever something misses the pot, I have to pop it in my mouth, one of my kitchen quirks. Where did it come from? Why do I always bite one corner of a bread slice before making it a sandwich? I don’t know. Maybe it’ll come to me one day when I’m cooking.

- Delano Burrowes prepares an African Peanut Stew | Photography by Kelly Torres

I’m finished cleaning and take out the cilantro to wash and chop. Cilantro is such a divisive herb, few people are ambivalent about it. I love it with a passion and add it to much of my Thai cooking. When I was in Chiang Mai, I took a cooking class with my best friend, Ryan. It was incredibly hot and humid in the outdoor kitchen – one woman fainted. But we were so deeply happy ’cause we were young and backpacking around a foreign country with no worries. The only thing we had to focus on was listening to our teacher explain how to chop cilantro.

When we returned home, Ryan became very lethargic and within a week was diagnosed with leukemia. He died three months later. I’m still sad, deeply sad, about his death, but as I write this I am also smiling while thinking about us chopping cilantro and laughing. Later, the students all sat on picnic tables eating our different versions of green curries, papaya salads and mango with sticky rice. I don’t remember what anything tasted like but it was one of the best meals of my life.

The cilantro is finished and my kitchen is full of spices and herbs dancing with each other: tomatoes on top of garlic and peanuts up against collard greens. I’m happy. Even before taking one bite of the meal, I’m happy. Now I eat.

Brooklyn, EAT your heart out!

- African Peanut Stew prepared by Delano Burrowes | Photography by Kelly Torres

“I love the flavors in this African Peanut Stew so much, especially in the colder months. It has a perfect balance of acid, fragrant spice, earthy richness and heat. Some African Peanut Stews have chicken but I prefer to let the vegetables take center stage in my version. It’s also a vegan meal that carnivores enjoy as much as non-meat eaters, which is good for dinner parties or potlucks. It’s a good recipe to play around with: Add chickpeas, roasted butternut squash, zucchini, etc – get creative and make it your own. Hope you have fun making it and even more fun eating it.” – Delano Burrowes

African Peanut Stew

- 2 tbsp olive oil

- 3 scallions

- 5 heads garlic, minced (but I LOVE garlic so you may want to do 3)

- 1 inch ginger, peeled and minced

- 2 medium sweet potatoes, peeled and chopped

- 3 grated carrots

- 2 tsp cumin

- 1/2 tsp cinnamon

- 1/8 tsp cloves

- 1/4 tsp cayenne

- 1 1/2 tsp chili sambal

- 1 can (28 oz) diced tomatoes

- 2 cups vegetable broth

- 2 cups collards (spinach and kale are also great)

- 1/2 cup frozen shelled edamame

- 1/2 cup unsweetened natural peanut, almond, or cashew butter

- Salt & Pepper

- Chopped cilantro

- 1/3 cup chopped peanuts

- Put on some music in the background – Miles Davis is alway my go – to cooking music – there’s just something about those tempos.

- In a large pot, heat the oil over medium heat. Add scallions, sauté for 3 minutes, followed by garlic, ginger, cumin, cinnamon, cayenne for 5 more minutes.

- Add sweet potato and carrots & cook for 10 minutes, occasionally stirring the vegetables.

- Add cumin, cinnamon, cayenne, sambal, tomatoes and vegetable broth. Bring to a boil then add collards and edamame.

- Reduce heat and simmer for 25 minutes.

- Stir in the peanut butter and mix until thoroughly blended. Adjust seasonings to taste and serve with crushed peanuts, cilantro , and anything else you choose: Couscous and raisins. Quinoa. Brown rice. Naan. Toasted pita. Cup of Greek yogurt mixed with 1/2 teaspoon of lemon juice and a pinch of cinnamon.

Leave a Reply